On Behalf of the Schaus’ Swallowtail

Contributed by Jaeson Clayborn*

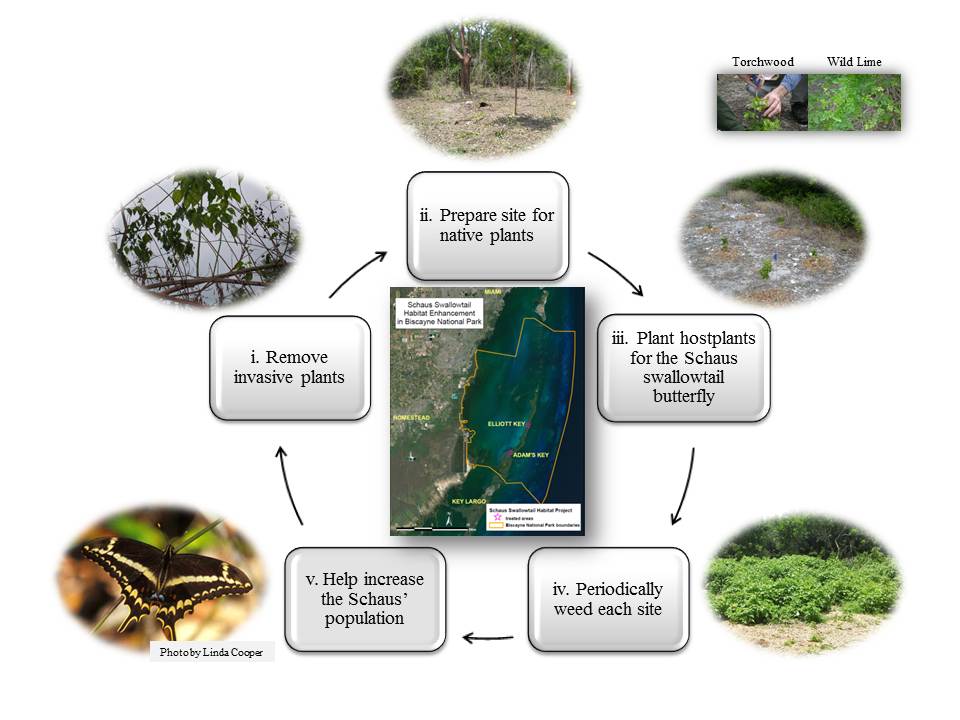

Abstract: The first part, “Habitat Enhancement at Biscayne National Park,” describes a project to protect and increase Schaus’ Swallowtail host plants (torchwood and wild lime) on Elliott and Adams Keys. The second part, “The Schaus’ Swallowtail: Florida’s First Federally-listed Endangered Butterfly,” provides in-depth descriptions of the butterfly’s life-history and historic efforts to protect it.

Habitat Enhancement at Biscayne National Park

The Schaus’ swallowtail butterfly (Heraclides aristodemus ponceanus) was listed as federally endangered in 1984, and until recently, was the only endangered butterfly in the U.S. In 1997, the butterfly reached an estimated population of 1,400 individuals. Since that time, the population has continued to decline and was estimated at 190-230 adults in 2002. In 2012, in a study conducted by the McGuire Center for Lepidoptera & Biodiversity, Florida Museum of Natural History, only 3 to 5 individuals were observed during the annual flight season.

The primary goal of the Schaus’ swallowtail butterfly habitat enhancement project is to increase the butterfly’s population by increasing the abundance of its food sources (host plants). Torchwood (Amyris elemifera) and wild lime (Zanthoxylum fagara), the butterfly’s only known larval hosts in South Florida, are not common on Elliott Key and Adam’s Key in Biscayne National Park (BNP), even though this is where the butterfly has been found historically in the highest numbers.

Torchwood and wild lime both occur naturally on Elliott Key and Adam’s Key; however, both plants tend to germinate and grow best along the edges and gaps of the subtropical hardwood hammock. Edges and gaps also tend to be exploited by fast growing invasive plants. If there are few host plant seedlings germinating, and if the gaps and edges of the hammocks are dominated by fast growing invasive plants, this could herald the eventual doom of the Schaus’ swallowtail.

I have had the good fortune to get involved in a project that aims to help this rare butterfly, proposed by Dr. Kevin Whelan (Principal Investigator, Community Ecologist, National Park Service, South Florida/Caribbean Inventory and Monitoring Network) and collaborators Tony Pernas (Program Coordinator, National Park Service, Florida and Caribbean Exotic Plant Management Team) and Vanessa McDonough (Ecologist, Biscayne National Park, National Park Service). Funding was provided by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service through the South Florida Coastal Program.

The objectives of the project are:

- Remove invasive plants from several restoration sites at Elliott Key and Adam’s Key;

- Replant the restoration sites with host and nectar plants specific to the Schaus’ swallowtail;

- Monitor the survivorship of the host plants and Schaus’ swallowtail by detecting the presence of caterpillars.

The Schaus’ swallowtail butterfly habitat enhancement project builds on ongoing and current projects that require particular sections within the hardwood hammocks at Elliott Key and Adam’s Key to be cleared of invasive plants. The majority of plants recently planted on the two Keys were torchwood and wild lime, along with some nectar plants, and a few other butterfly host plants including corkystem passionflower (Passiflora suberosa), balloonvine (Cardiospermum corundum), and cowpea (Vigna luteola). All these species were strategically planted throughout the cleared sites to encourage habitat diversity.

So far in 2012, NPS staff, interns, and volunteers (including a Sierra Club work day, see picture) have spent over 1,536 hours in the field (most of these hours accruing from volunteers). They have planted 906 seedlings, mainly torchwood, at Adam’s Key and 1,426 seedlings at Elliot Key. Continued maintenance has been implemented to minimize weeds because they can quickly shade out the torchwood seedlings. Weeding is a twice monthly ordeal; during the wet season, when everything grows verdantly, it can seem like nothing was done on the previous visit. Once the two main restoration sites (previously occupied by exotic Burma reed (Neyraudia reynaudiana) and latherleaf (Colubrina asiatica)) are completely filled with native plants, more torchwood and wild lime will be planted in natural gaps and along trails that occur throughout the two Keys. Hopefully, several years from now, we will see an increase in Schaus’ swallowtail sightings at Elliott Key and Adam’s Key.

Even though many of us have lives that are too busy, anyone can have a positive impact on butterflies in their community by planting host plants for butterflies that occur in that area. For example, if you plant citrus plants, you are likely to attract giant swallowtail butterflies. Perhaps the greatest bang for the buck can be had by planting corkystem passionflower (Passiflora suberosa) in the yard; it attracts zebra heliconian (Heliconius charitonius, Florida’s state butterfly), Julia (Dryas iulia), and gulf fritillary (Agraulis vanillae) butterflies. The Schaus’ swallowtail project provides educational and research opportunities for visitors and scientists who travel to the keys in Biscayne National Park. Everyone involved in the Schaus’ project, including people who plant host and nectar plants for butterflies in their yard, are active conservationists, as we all do our part to increase habitat for native butterflies.

Sierra Club workday, Elliott Key, August 11 2012

Sources for additional information

Gast, P. (2012, June 13). Biologists, volunteers rush to save Florida butterfly species.CNN U.S. Retrieved from http://articles.cnn.com/2012-06-13/us/health_florida-endangered-butterfly_1_miami-blue-jaret-daniels-Schaus’-swallowtail?_s=PM:US

NPT Staff. (2012, June 17). Dwindling Numbers Of Schaus’ Swallowtail Butterfly In Biscayne National Park Lead To Collecting Decision. National Parks Traveler: Commentary, news, and life in America’s Parks. Retrieved fromhttp://www.nationalparkstraveler.com/2012/06/dwindling-numbers-Schaus’-swallowtail-butterfly-biscayne-national-park-lead-collecting-decision1006.

* Jaeson Clayborn is a NABA member and doctoral student in biology at Florida International University.

The Schaus’ Swallowtail:

Florida’s First Federally-Listed Endangered Butterfly

Biscayne National Park, along with remnants of subtropical hardwood hammock on North Key Largo, is the only known refuge in the U.S. of Florida’s only federally endangered butterfly, the Schaus’ Swallowtail. In the Caribbean, where suitable habitat has persisted, it may be found in the Bahamas, Turks and Caicos, Puerto Rico, Hispaniola, Little Cayman Island, and Cuba.

The Florida race, Heraclides (=Papilio) aristodemus ponceanus, is endemic to this small sliver of subtropical South Florida. That is, this butterfly exists nowhere else on earth but in Biscayne National Park, on the keys a few miles across Biscayne Bay, and on North Key Largo. It relies on specific trees of the hammock, Torchwood (Amyris elemifera) and Wild Lime (Zanthoxylum fagara).

Schaus’ Swallowtail by Linda Cooper |

Torchwood (Amyris elemifera) |

Life Cycle: Although she may lay hundreds of eggs in her brooding season, the adult female Schaus’ lays but one, maybe two, eggs at a time on a leaf tip in a shady area of the hammock. This dispersal of an egg here or there is one strategy to foil predators and other threats. There is no “mother load” of eggs to be wiped out in one deft attack or other calamity.

Even so, only about 30% of eggs survive to hatch. After 3-5 days, caterpillars emerge and forage their way, usually solitary, through the tender new leaves of Torchwood and Wild Lime. Like some other swallowtail butterflies, the Schaus’ caterpillar attains a good size and is disguised to resemble bird droppings to confuse predators. Nevertheless, only about 5% survive predation and other hazards in the hammock to make it to the pupal stage.

When it is time to pupate, the caterpillar strikes out, again alone, to secure itself, well camouflaged, to some hidden object in the woods, where it transforms into a chrysalis. The pupa, or chrysalis, can remain in diapause for up to 2 years, awaiting the proper conditions for the new adult to emerge: rain and new plant growth.

In the wild, the adult survives an average of 3.5 days – and obviously has much to accomplish in a short time: nectaring, mating, egg-laying. In protected laboratory conditions, free of predators, harsh weather, and human impacts, adult Schaus’ can live a month or more.

Schaus’ Swallowtails mainly nectar on 8 plants: Mouse’s Pineapple (Morinda royoc),Blue Porterweed (Stachytarpheta jamaicensis), Sea Grape (Coccoloba uvifera), Scorpionstail (Heliotropium angiospermum), Snow Squarestem (Melanthera nivea),Wild Sage (Lantana involucrata), Wild Coffee (Psychotria nervosa) and Guava (Psidium guajava).

The fortunate observer who sees an adult Schaus’ can expect a butterfly on the move. Rarely found perching or pausing to nectar, males patrol edges of woods and trails, seeking females. Meanwhile, the sought-after females are likely to be in the hammock interior, seeking caterpillar host plants.

Jeopardy: Discovered in Miami in 1898 by Dr. William Schaus, a Spanish-American War physician, the butterfly was scientifically described in 1911 from specimens collected in South Miami-Dade County. At the beginning of the 20th Century, it ranged from Miami to the tip of the Florida Keys.

Barely identified and catalogued, the Schaus’ was last seen on the Florida mainland in 1924 and was losing ground in the Middle and Lower Keys as early as the 1930’s, as hammocks were felled by hurricanes and land developers. In the 1940’s, 1950’s and 1960’s, although concentrated in a very few small pockets in the Upper Keys, and still collected, the Schaus’ nevertheless persisted in good numbers until the early 1970’s.

Then the population crashed, overwhelmed by the cumulative impacts of heavy collecting, hurricane damage to subtropical hardwood hammocks, loss of habitat to development, and intensified aerial mosquito spraying with heavier toxins in the 1970’s.

In 1976 the Schaus’ was federally listed as Threatened, and, as its numbers continued to decline, in 1984, it became one of a small number of butterflies listed as federallyEndangered.

Concurrent with its designation as federally endangered, the US Fish & Wildlife Service contracted with the University of Florida for a status survey. At this point, the butterfly found a tenacious advocate in Dr. Thomas Emmel, Professor of Zoology and then the Director of the Divison of Lepidoptera Research at the University (and now the Director of the McGuire Center for Lepidoptera and Biodiversity, Florida Museum of Natural History).

Emmel and his colleagues, including Dr. Jaret Daniels, now Assistant Director of the McGuire Center, set to work. First they established the dire straits of the Schaus’: fewer than 70 adults flew in 1984, limited to off-shore keys within Biscayne National Park and a tiny segment of North Key Largo. Second, they undertook an exhaustive study of the many factors that might account for the Schaus’ demise.

This time, the precipitous decline was due much less to collecting and storms, but rather, as documented by Emmel and his colleagues, new and more lethal methods of mosquito control. The adult Schaus’ Swallowtail emerges from its chrysalis and deposits its eggs once a year; caterpillars follow shortly to feed and grow. This cycle is concurrent, unfortunately, with the first rains that bring new growth to Torchwood and Wild Lime, and that also herald the beginning of “mosquito season” – in May and June.

Responding to advancing development of upscale housing and amenities in the Upper Keys in the 1970’s, and concurrent resident demand, the county was intent upon eradicating mosquitoes. Throughout the Keys, powerful insecticides were zealously applied at concentrations several hundred times more than needed to kill adult mosquitoes (and other adult insects).

Spraying often occurred at times of day when citizens could see action being taken, but when the crepuscular (dusk-flying) mosquitoes were missed, and the diurnal (day-flying) insects such as the Schaus’ and other butterflies were active. This, Emmel and his team concluded, was the driving force pushing the Schaus’ ever-closer to extinction after its 1984 listing as federally endangered.

Conservation: Emmel and his team took action; they convened a 1991 symposium at the University of Florida that was instrumental in the discontinuance of lethal Baytex, tempered the quantities of other chemicals used, and halted aerial mosquito control on federal and state land in North Key Largo. The Schaus’ again had a new lease on life. However, due to its small numbers, restricted distribution, and the obvious threat that one hurricane could destroy the entire population, it needed help beyond relief from toxins.

Captive propagation and re-introduction was approved by the Fish and Wildlife Service in the nick of time! In June 1992, Emmel’s team fortuitously removed 100 wild eggs from Biscayne National Park and began rearing Schaus’ Swallowtails in Gainesville laboratories. In August 1992, Category 4-5 Hurricane Andrew flattened much of South Dade County, including the hammocks of Biscayne National Park and Upper Key Largo. Emmel’s team of 8 researchers found a meager number of emerged adults in the spring of 1993 – but their Schaus’ ace-in-the hole was safe in Gainesville.

As it turned out, in the spring of 1993, hammocks open to the sun produced abundant lush new growth of Torchwood and Wild Lime and small numbers of wild adult Schaus’ had a very high reproduction rate – a not uncommon occurrence in an otherwise healthy environment following a natural disaster.

Throughout the 1990’s, Emmel’s captive breeding and re-introduction program persisted, despite a long list of obstacles owing to funding and public agency priority shifts. Occasionally, Mother Nature exerts influence, as in 1995, when inclement weather produced a “sit down” of migrating song birds, which gratefully ate most of the pupas Emmel’s team had placed in the hammocks.

Nevertheless, in 1996 and 1997, 1200 to 1400 Schaus’ were tallied. Things were looking good.

In the early years of this decade, in the Keys, two golf courses, a national wildlife refuge, and fisher’s club entered into partnerships with the US Fish and Wildlife Service and the McGuire Center to create Schaus’ habitat. Public education programs evolved. Perhaps the Schaus’ Swallowtail was on the road to recovery and even de-listing as endangered.

Change of fortune: In 2002 and 2003 only a couple of hundred adult Schaus’ were estimated by Emmel and Daniels (2005). Annual counts in May for Elliott Key in Biscayne National Park, by Mark Salvato for the North American Butterfly Association, recorded as low as 2 and only as high as 26 in the years 2004-2008.

Hence, after a brief surge in the 1990’s attributable to re-introduction success, the Schaus’ is once again imperiled. Many factors are arguably at play.

The remaining Schaus’ Swallowtails in North Key Largo confront continued loss and fragmentation of habitat due to hurricanes and development, public demand for mosquito spraying, spray-by-wind-drift from developed areas into “no-spray” zones, other chemical contaminants other than insecticides in the environment, non-native parasitoids and predators, notably exotic Fire Ants.

On Elliott Key, in Biscayne National Park, the population faces fewer risks, but one catastrophic hurricane, disease, or onslaught of predators or parasitoids could topple the Schaus’ into extinction.

Species of smaller animals, including butterflies, are still being discovered. Given that it disappeared from mainland Florida only 13 years after it was scientifically described, the Schaus’ provides an example of a butterfly that could have escaped attention and become extinct without our ever knowing it existed.

Conservation International estimates that one species will go extinct every 20 minutes. Our Schaus’ Swallowtail is in danger of joining this sad statistic on our watch, teaching us once again that it is far better to conserve before we get to the brink than to try to return from the brink.

The Schaus’ options depend on us: Can anything be done to protect our existing, endangered Schaus’ Swallowtail and restore vigorous populations? Each of the proposed solutions require public and private organizations and agencies to cooperate – and for that to occur, our voices as individuals need to be heard by our elected officials and our local, state and federal agencies.

Additionally, we can exert influence by joining and supporting organizations that seek to acquire lands for habitat or seek to influence public policy in pro-environmental directions. Specifically, we can and should use our influence to encourage:

- Elimination of exotic, predatory ants from Schaus’ habitat.

- Captive breeding to offset potential hurricane destruction.

- Prohibition of mosquito abatement methods that produce drift into protected Schaus’ habitat.

- Larval, rather than adulticide-based, mosquito control.

- Restoration of suitable Schaus’ habitat and host plants where it has been lost and where it can co-exist with human development.

- Implementation of frequent surveys of Schaus’ distribution and abundance throughout its range as the measure of the effects of our activities.

Sources:

Emmel, T. C. (1994). Schaus’ Swallowtail: A beleaguered aristocrat teeters on the edge of extinction in the Florida Keys. American Butterflies, 2(1): 18-22.

Emmel, T.C. and Daniels, J. C. (1997). Is Schaus’ Swallowtail finally licked? American Butterflies, 5(2): 20-27.

Imperiled Butterflies of South Florida Work Group (2009). Statement on the decline and loss of butterfly species in Southern Florida: DRAFT.

US Fish & Wildlife Service, Southeast Region (2007). Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants: 5-Year Review of 22 Southeastern Species (http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/getdoc.cgi?dbname=2007_register&docid=fr26ap07-75).